Catholic Church flip-flops on ‘the vulnerable’

The Catholic Church in Australia is reeling from revelations at the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, of a shocking number of cases that have occurred under its ‘pastoral umbrella.’ Yet it presumes to tell the rest of us about the hypothetical moral dangers of assisted dying laws for ‘the vulnerable.’

To add insult to injury, it flip-flops on its stance.

Never mind that the argument is contradicted by evidence

The Church’s favourite argument — already contradicted by scholarly analysis that curiously seems to be of no interest to the Church — is this: if people are given the choice of assisted dying, they will feel compelled to choose it, coerced by doctors, greedy relatives or others; subtly or otherwise.

No matter that health care workers routinely report that relatives usually try and persuade their dying loved one to endure yet another invasive and burdensome treatment; not dissuade them from it.

The flip-flop

If the Catholic Church were indeed genuinely concerned about coercion of ‘the vulnerable,’ then it would equally oppose the right to refuse medical treatment, particularly if the treatment were life-prolonging. But it doesn’t.

If granny might die as a result of refusing a particular medical intervention, then a doctor might persuade her to refuse in order to conserve medical resources. Or greedy relatives might persuade her so that they are relieved of the burden and expense of looking after her and gain earlier access to her estate.

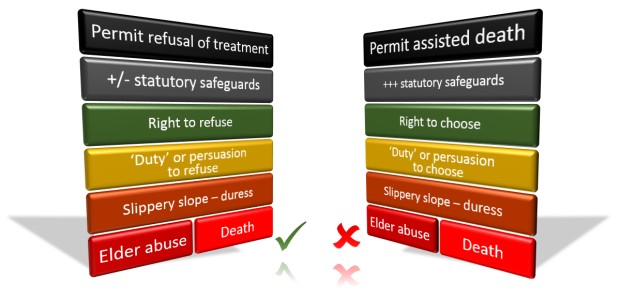

As eminent legal scholar Gerald Dworkin has argued,1 if there’s a theoretical ‘slippery slope’ for assisted dying, it’s the same for the refusal of life-preserving medical treatment.

To hold different positions under the same risks is to flip-flop. That’s especially so when there are numerous safeguards built into assisted dying statutes, but currently few or none for the right to refuse life-preserving medical treatment.

The Catholic Church approves of the theoretical risk of the left-hand course (refusal of life-saving medical treatment), but not of the theoretical risk of the right-hand course (assisted dying) which is lower in practice by virtue of considerably more statutory safeguards.

The Catholic Church approves of the theoretical risk of the left-hand course (refusal of life-saving medical treatment), but not of the theoretical risk of the right-hand course (assisted dying) which is lower in practice by virtue of considerably more statutory safeguards.

Local experience confirms risk is theoretical

In my home state of Victoria, where the right to refuse any unwanted medical treatment has been enshrined in statute for nearly three decades (the Medical Treatment Act 1988), how many prosecutions have there been under the Act’s provisions against inappropriate persuasion?

Precisely none. Not a single case. So much for the theory.

It all serves to highlight that the Catholic Church’s only real argument is that it believes that it’s morally wrong to deliberately hasten death. However, it avoids this argument because as a religious tenet, it doesn’t appeal to the masses.

Catholic directives

The Church’s flip-flop about ‘the vulnerable’ is not a one-off accident. Take for example the ‘Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services’ published by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.2

The Bishops ‘direct’ that there is no obligation on patients to use disproportionate means of preserving life. They state that disproportionate means are:

“…those that in the patient’s judgement do not offer a reasonable hope of benefit or entail an excessive burden, or impose excessive expense on the family or the community.”

The Bishops further ‘direct’ that:

“The free and informed judgment made by a competent adult patient concerning the use or withdrawal of life-sustaining procedures should always be respected and normally complied with, unless it is contrary to Catholic moral teaching.”

Setting aside the Church’s hubris of dishonouring the patient’s choice if the Church disagrees, it would be theoretically easy for someone to persuade the patient that hope was not reasonable, that the burden would be too great, or that the cost to the family or society would be too high.

Suffering for our God’s (your own) good

On the next page, the Bishops expressly ‘direct’ that:

“Patients experiencing suffering that cannot be alleviated should be helped to appreciate the Christian understanding of redemptive suffering.”

That’s unqualified. So, if you’re atheist, agnostic, Jewish, Hindu, Muslim or even a Christian who believes assisted dying can be appropriate, as a patient in their institutions you are to be persuaded that suffering against your beliefs and wishes is ‘redemptive’ in the eyes of the Vatican’s version of a God.

In Australia in 2009, for the Office for Family and Life in the Catholic archdiocese of Adelaide, Mr Paul Russell argued in News Weekly that “there is a point to suffering” because:

“It’s about the profound connection that each and every life has to the incarnate God … We know that the sufferings we endure well are joined in some mysterious way to the sufferings of Christ.”

Pity any poor soul who doesn’t share Mr Russell’s views. Curiously, there is no mention of this underpinning belief in his anti-assisted dying blog, “HOPE.”

Invalid argument in any case

The Church’s argument that ‘the vulnerable’ will be ‘at risk’ from assisted dying laws — for example in the Victorian Bishops’ recent pastoral letter to the Catholics of Victoria opposing the upcoming assisted dying parliamentary Bill — is itself fundamentally invalid.

That’s because, as I’ve previously explained, it’s a circular argument: a logical fallacy.

A circular argument: We must ban yellow socks on Wednesdays or the 'vulnerable' will be 'at risk'.‘The vulnerable,’ by definition are those ‘at risk,’ and will still be so if we wear yellow socks on Wednesdays. Therefore, we should ban such bright footwear midweek — and anything else we happen to oppose — on the same basis.

Might anyone suggest that “we should ban religion because the vulnerable will be at risk of succumbing to extreme religious views”?

Will the Church change its mind?

The Catholic Church does change its mind from time to time, though its reforms are glacially slow.

Take, for example, its theory of limbo, a place on the doorstep of hell where, the Church claimed, babies go if they die before they’re baptised: that they’d be prevented from entering heaven. It would be hard to imagine a crueller worry to put into the heads of uneducated new parents.

But in 2007, after centuries of confidently promoting the theory, the Catholic Church decided that it was wrong and buried it.

Will it change its mind on assisted dying? Maybe, but don’t hold your breath.

Conclusion

The Catholic Church, reeling from its extensive failure to protect our most vulnerable — children — and notwithstanding some good individuals within, still presumes to morally lecture the rest of us with the logical fallacy of how ‘risky’ assisted dying legislation is supposed to be to ‘the vulnerable,’ while flip-flopping in support of refusing life-saving medical treatment under the same theoretical risk.

The Bishops’ rhetoric amply exposes their confected crisis against assisted dying as nothing but religious doctrine draped in faux secular garb… in reality a sheep in wolves’ clothing.

References

- Dworkin, G, Frey, RG & Bok, S 1998, Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York. pp.66ff

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops 2009, Ethical and religious directives for Catholic health care services, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Washington DC, pp. 43, https://www.usccb.org/issues-and-action/human-life-and-dignity/health-care/upload/Ethical-Religious-Directives-Catholic-Health-Care-Services-fifth-edition-2009.pdf.